Click here for interactive experience (desktop recommended.) Use curser to explore image references.

Read full text

In The Allegory of the Cave, Plato asks us to imagine a group of prisoners trapped in an underground cave. These prisoners have been there since birth, with their legs and necks chained so they cannot move. The prisoners watch shadows projected on the wall from objects passing in front of a fire behind them. The shadows represent the prisoners’ reality. Over time they come to recognize the different shadows and attach names to them. They even create games with each other over who can guess which shadow would turn up next and give honor and praise for the one who can guess the best.

One day, one of the prisoners escapes. The chains on his neck and legs break off, allowing him to stand up for the first time. He looks around, confused by the surroundings. He then begins to walk and examine everything around him. The freed prisoner sees the fire and objects next to it, and even recognizes some of them from the shadows he had seen. He realized that the shadows must have come from these figurines, and in fact, it is these objects that are the greater reality that created everything he perceived before. The prisoner then carries on walking and wanders out of the cave.He sees the Sun, the trees, the animals, and everything around him for the very first time. He realizes that up until then, he did not know what true reality was. The shadows are just signs of a tiny part of the greater reality, and there is much more to life than what he had been perceiving. He then goes back to the cave to inform the other prisoners about the greater world outside, only to be ridiculed and shamed by them, because they refuse to imagine a world different from their absurd misrepresentation of reality.

In this parable, Plato embeds a more significant allegory of his, which is the world of forms. One can easily draw the connection and realize that the cave is the physical material world we live in, while the world of forms is the one beyond the cave. The philosopher is the freed prisoner who sees both worlds. One allegory imposes itself on the other, like one shadow being cast on the one beneath it.

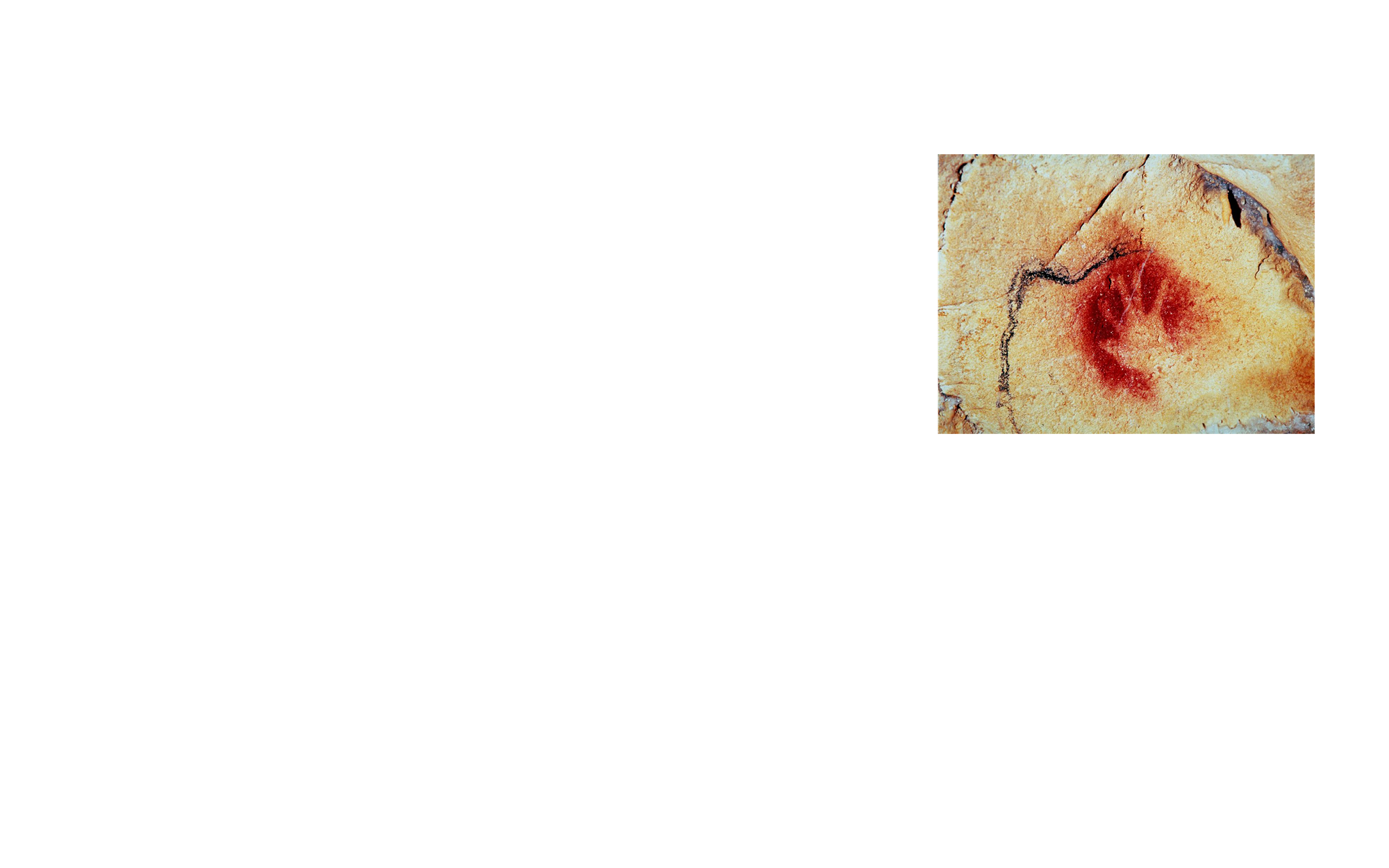

As prisoners imprisoned in the material world, we have a bit more liberty than the ones pictured in Plato’s story. We are able to impose our perception of almost anything onto this material world that we live in. Our ancestors left the cave paintings as representations of their era: the galloping horses, battles of wild beasts, or a handprint of a man. Someone from the ice age most likely created this image by spitting red pigment over a hand pressed against the rock. It is the stencil of a hand, demonstrating a gesture of capturing a moment and cementing it while being captured for eternity. Of all the vivid paintings in the cavern of Chauvet, this image of a hand is the most loyal and realistic reflection of our kind. Consciously or unconsciously, it is in this cave that the painter happened to experience a close encounter with something from Plato’s world of forms. The beauty of art, a hint of self-awareness that distinguishes humans from animals, or a spark of existentialism. Can we see this as an attempt to question the cave or the reality? Is it a symbol of a myth, or is it just an image of a human hand?

It is an image of this hand that marks the end of the film, Cave of Forgotten Dreams, a documentary shot in 2010 by German filmmaker Werner Herzog. He and his crew of three were the first to film the interior of the cave of Chauvet. Asleep over millennia, far away from progress and evolution, the remains of prehistoric life were frozen when a landslide blocked the entrance, and the salty tears of the cave preserved the original drawings in a blanket of calcium. Images were etched, smeared, blown, and drawn onto this undulating, ragged, curved surface so that topography blurs into figures—the surface of a sleeping bison, the neck of a horse conjured by shading applied to a fissure or a bump. Thanks to the contrasts and ingenious graphic expressions that suggest motion, the static figures revive and appear to feel the impetus that inspired successions of artists to paint them : their fury is revealed in their eyes, the emotion in their muscles, and they return in these images to their eternal struggle for survival. At one point in the film, the director of photography began to film their shadows on the wall, making their dark silhouettes stand side by side with the figurations of extinct animals. A caveman could have done the same with the light of his torch. The present and the past overlapped at this very moment. For the paleo-artists, the cave is the endless space of representation, which is applied to the world itself and becomes signs of the world. And these prehistoric signs continue to communicate with their audience, as they have been for tens of thousands of years.

However, for Herzog, interpreting the remains of ancient life from a modern point of view is a profound paradox. His candid perspective reminds us that our will and our tools for comprehension may be totally inefficient when approaching the paleo-world. Everyone can project their own understanding onto the paintings, the cave, or the trembling pixels that represent them. If so, the sign no longer bears any meaning, for it has become ambiguous over time, like an unidentifiable blurred image projected through a wrong lens onto the screen.

But are we stepping into the pitfall of nihilism, where reality does not exist? Are we back into Plato’s cave, or did we ever leave it, to begin with? What would Plato and the prisoners in his story think of the Chauvet Cave? To better understand the paintings in the cave, Herzog stepped out of it to interpret signs of an ancient life expressed in a cryptic language while questioning his own capacity to interpret. The present reality is not a finality, but rather only one layer of history and not necessarily even a progression within it. A shadow, casting onto the signs of the past, forges another layer over reality. Can we ever manage to grasp the essence of it through deciphering signs within the existing symbolic system? Or are the signs the essence itself, echoing in the chambers of the cavern?

These questions and attempts to answer them are similar to the game that the prisoners have in confinement, though what they question is not the reality but its signs. In Kimura Kyūho’s On the Mysteries of Swordsmanship, the master proposes that “reality itself is not a sign, and it leaves no tracks. It does not come to us by way of letters or words. We can go toward it by following those words and letters back to what they came from. But so long as we are preoccupied with symbols, theories, and opinions, we will fail to reach the principle.” If the freed prisoner does not recognize the objects from the shadows he had seen, he would not realize the difference between signs and reality, and would never have the vocation to explore the world beyond his cave.

What about the cave that we are confined in now? The shadow is changing so rapidly that we can barely get a hold of its appearance, let along what it truly represents. What would the ice age artist think if he enters Richard Hamilton’s image of a modern cave, one full of pop culture and commercial information? Would he be as confused as we are when confronting his legacy? The void between object and representation is further extended, stretched, and even twisted over temporospatial distance. Is it the treachery of the signs, or the reality? Maybe there is hardly any difference between this inseparable duo. The representation, or the spectacle, according to Guy Debord, “is a worldview that has actually been materialized, that has become an objective reality.” The shadows on the wall become fossilized strata with physical presences, overruling the reality.

In The Order of Things, Foucault argues that the sign “has no other content in fact than that which it represents, and yet that content is made visible only because it is represented by a representation.” The habitual divorce of reality and representation cultivates the sign. Signs are the layering shadows that construct our reality. Unlike the freed prisoner who goes outside the cave for his quest, we may find the answers to reality right back in the artificial caves of our own, in the void between shadows and reality.